Note also, we break up the 17 decades.Īs in the lab for Module 1, we begin with some practice questions that you can take in the Lab 2 practice submission, where you will receive the answers to the questions. Also, there are a few storms including Betsy whose names do not show unless you zoom in close. Please make sure that the slider at the top left has the relevant range of dates on it, otherwise, you will not be able to view tracks for the desired storm.

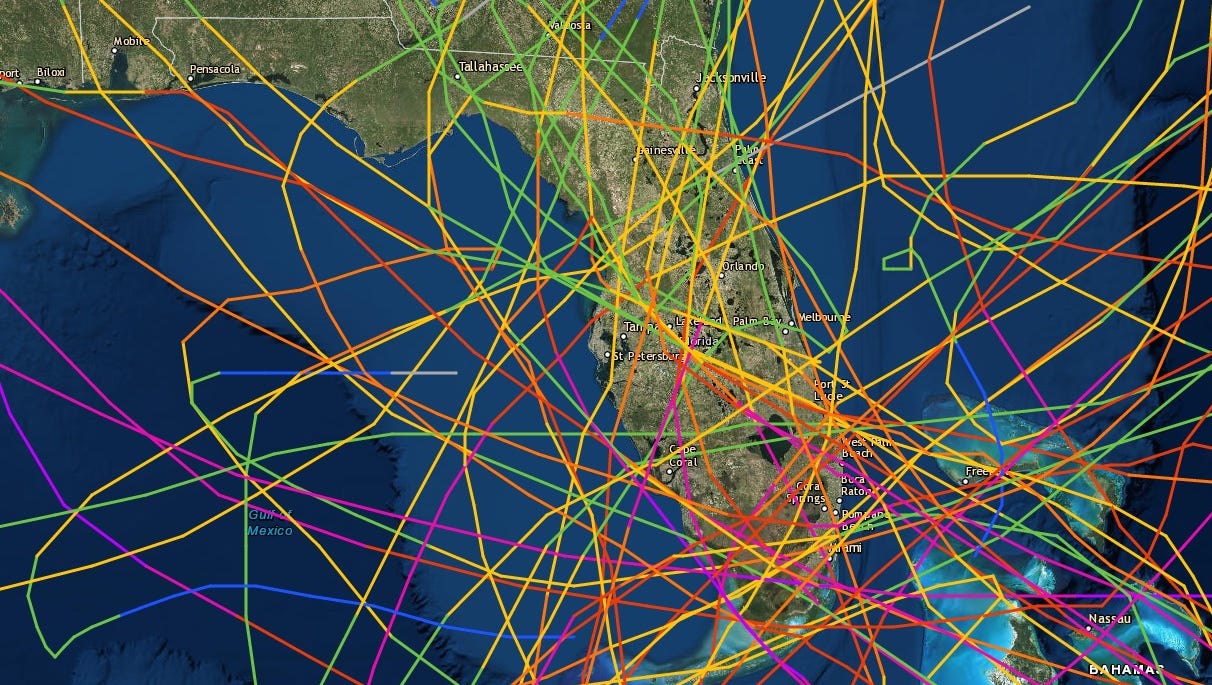

We definitely recommend that you don’t try to look at the storms all at once or you will see a maze of lines. The storm tracks have points that show the wind speed and pressure at different stages in its development. Both maps have sliders at the top left of the screen that allow you to look at storms as well as temperature over time. You can switch back and forth between maps. The second, Temperature Anomalies kmz file, shows average August temperatures for each year calculated relative to the average temperature between 19. There are two Google Earth maps to load, the first, Hurricane Tracks kmz file, shows tracks of storms from 1900 to 2017. to observe the relationship between storm intensity and warming.to determine the main causes of damage from storms including wind, rainfall and flooding, and storm surge.In this lab, we will observe the tracks of the largest storms of the last century, and learn about the impacts of those storms on land.

HURRICANE TRACK MAPS HISTORY DOWNLOAD

Rohde, Global Warming Art.Download this lab as a Word document: Lab 2: Hurricanes (Please download required files below.) To learn more about hurricane formation, climatology (including the relationship between global warming and hurricanes), and NASA’s hurricane research activities, please read the Earth Observatory’s newly updated fact sheet, Hurricanes: The Greatest Storms on Earth. Storms that have survived to these latitudes often swing back to the east before falling apart. Farther from the equator, in the mid-latitudes, westerly winds are more common. In the tropics, the storms move with the prevailing easterly winds that occur in both hemispheres. The map also reveals the general atmospheric “steering” influences on hurricanes. The South Atlantic off the east coast of Brazil isn’t favorable for hurricanes for a variety of reasons, including prevalent wind shear (variation of wind speed or direction at different altitudes.) In 2004, a rare-perhaps unique-tropical cyclone formed in this region, eventually making landfall in Brazil the track of this storm, Hurricane Catarina, stands alone in the South Atlantic. A similar cold current, the Benguela Current, flows up the western coast of South Africa, past Namibia and Angola, keeping those waters too cool for hurricanes as well. The cool current keeps waters from reaching hurricane-friendly temperatures. To the west of South America, the Peru Current snakes northward along the coast of Chile, Peru, and Ecuador, bringing cool water from southern polar regions. Although frequent thunderstorms do occur at the equator, the air rushing into the low-pressure centers of these storms doesn’t get the needed “spin” from the Coriolis force, and so the storms don’t develop the large-scale rotation that sets them on the path to becoming hurricanes.Īnother obvious feature is the lack of tropical cyclones in Southwest Pacific and South Atlantic Oceans. The Coriolis force is strongest near the poles, and zero at the equator. Instead, the Coriolis force spins moving air to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and to the left in the Southern Hemisphere. The force keeps air from moving in a straight line across the surface of the Earth. The Coriolis force results from the Earth’s spherical shape and its rotation. The absence of hurricanes at and very near the equator reveals another important factor in hurricane development: the Coriolis force. The blues and light yellows reveal storms in a weaker state: near the equator, in their first stages of development over land, as they run out of steam in the mid-latitudes, where they encounter cooler waters.

Over time, the repeated passage of strong storms through the same regions creates solid swashes of color: bright red in the Western Pacific near the Philippines, where numerous Category 5 storms have traveled orange and gold in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, where Category 3 and 4 storms often pass. The accumulation of tracks reveals several details of hurricane climatology, such as where the most severe storms form and the large-scale atmospheric patterns that influence the track of hurricanes. The map is based on all storm tracks available from the National Hurricane Center and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center through September 2006. Like streamers of splattered paint, the tracks of nearly 150 years of tropical cyclones weave across the globe in this map.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)